Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | TuneIn | RSS

Turning over the last page of the calendar seems to naturally invite some reflection on the previous 365 days. When you look back at 2017, what went well? And what do you wish you could change in the coming year?

This week, we take the opportunity to reflect back much farther – to our days in graduate and postdoctoral training! With years of hindsight, we offer advice and perspective to the scientists we were, and devise some resolutions you can adopt in your scientific training.

Grad School Resolutions

1. Remember that training is temporary

When you’re ‘on the inside,’ graduate training can seem like an endless tunnel – the light at the end just a distant pin-prick. For many, the daily stress of lab life closes in and we begin to feel trapped and hopeless. This year, pause to consider that your training is just a brief step in your scientific career, and that people do finish! We promise!

2. Be mindful of your unique skills and motivations

Many students wait to think about a suitable career until they have a degree in their hands and a PI’s foot on their backside. We recommend taking stock of your natural motivation and skill patterns early AND often.

It can be as simple as reflecting at the end of the day or on a Friday afternoon. What did you accomplish this week? Which activities left you feeling energized? Which left you drained? When did you lose track of time because you were engrossed in the task? Jot each item in a notebook or on a post-it and save them.

After a few months, you’ll have a detailed list of skills and activities you like to use and those you’d like to avoid. These patterns can persist over a lifetime, so spend some time examining the notes and identifying the common themes. That way, when you’re reading job postings, you’ll know exactly which positions fit your personality.

3. Push beyond your comfort zone

Starting a graduate program often means moving to a new town, meeting hundreds of new people, and dropping the support networks you enjoyed in college. That makes many introverted science-types turn further inward as we try to avoid the stress of new situations.

But remember that many of the people you meet feel exactly the same way. Push yourself to engage, and you’ll be rewarded with new friends and colleagues that will last a lifetime. Graduate training is full of never-to-be-repeated opportunities if you’re willing to step up and take them.

4. Make science fun again #MSFA

Don’t forget that you chose a career in science because science is amazing. Maybe it fascinated you as a child, but we quickly lose that child-like curiosity the moment Figure 4 of our paper is due.

Every once in awhile, it’s okay to let loose and try an experiment because you think it’s fun, or you just can’t predict how it will turn out. This will not only stoke your love of science, it may lead to your next line of inquiry.

5. Find emotional support before you think you need it

Graduate training may be one of the most stressful periods of your life. That’s not unusual. But too many of us try to ‘power through’ on our own. Anxiety, depression, panic attacks, and worse are the rewards.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Your mental health is as vitally important as your physical health. If eating right and going to the gym are admirable, then so are finding a counselor or mental health professional to help you on this journey. As we look back over our own graduate training, we wish we had found this support sooner.

So that’s it – five resolutions for a happier, healthier, sciencier you. Leave a comment below to let us know YOUR New Year’s Resolutions, or the advice you wish you’d gotten as a grad student or postdoc.

Shock Lobster

Science in the News gets metaphysical this week, with a report that Switzerland recently banned the boiling of live lobsters. We reveal the science, and speculation, of nociception in crustaceans and how it impacts your surf ‘n turf.

Well, at least the ‘surf’ part.

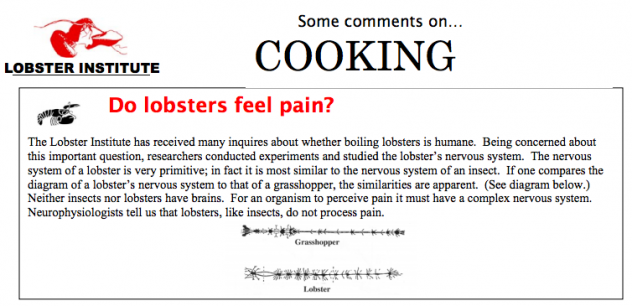

UPDATE: We quoted The Lobster Institute’s guide to cooking lobster in this episode. They write:

The nervous system of a lobster is very primitive; in fact it is most similar to the nervous system of an insect. If one compares the diagram of a lobster’s nervous system to that of a grasshopper, the similarities are apparent. (See diagram below.) Neither insects nor lobsters have brains. For an organism to perceive pain it must have a complex nervous system. Neurophysiologists tell us that lobsters, like insects, do not process pain.

Listeners pointed out that insects DO in fact have brains, thank-you-very-much. In fact, you can see detailed images of a fruit fly’s brain right here. This leaves us questioning the scientific basis for the Lobster Institute’s other claims, and questioning the nature of reality in general. #FakeNews

We also sample the Elevated IPA from La Cumbre Brewing in Albuquerque, NM. Yes, you read that right, IPAs ARE BACK, BABY!

And finally, this great quote from Peter Medawar about the beautiful, inspiring diversity of scientists and their passions for learning:

There is no such thing as a Scientific Mind. Scientists are people of very dissimilar temperaments doing different things in very different ways. Among scientists are collectors, classifiers and compulsive tidiers-up; many are detectives by temperament and many are explorers; some are artists and others artisans. There are poet-scientists and philosopher-scientists and even a few mystics. What sort of mind or temperament can all these people be supposed to have in common? Obligative scientists must be very rare, and most people who are in fact scientists could easily have been something else instead.

“Hypothesis and Imagination” (Times Literary Supplement, 25 Oct 1963)

Happy 2018 Friends, and Thanks for Listening!