Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | TuneIn | RSS

But I have no skills! At least no skills employers would be interested in!

As a career counselor, Melanie Sinche heard grad students and postdocs voice this concern nearly every day. She looked at these talented scholars and saw the ability to think critically, analyze data, and solve problems. To her eye, these were transferable skills very much in demand outside the research lab. Why couldn’t the students see it?

“I felt frustrated by that comment, and motivated to conduct a research study around skill development. I would argue that scientific training, by its very nature, lends itself to the development of LOTS of skills.”

Data Wins Arguments

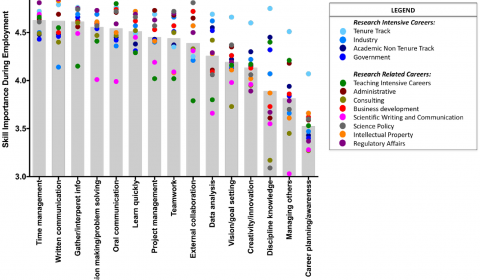

Sinche developed a survey for early PhDs who had entered the workforce, to find out which skills they needed to do their current jobs, and how well their graduate training had prepared them. Over 8,000 responded.

“It’s important for PhDs to recognize and have the confidence to express the skills that they’ve developed through their training,” Sinche says.

Here are the 15 skills, ranked by how well prepared the PhDs felt after their graduate training (Most Prepared to Least):

- Discipline specific knowledge

- Ability to gather and interpret information

- Ability to analyze data

- Written communication skills

- Oral communication skills

- Ability to make decisions and solve problems

- Ability to learn quickly

- Creativity/innovative thinking

- Ability to manage a project

- Ability to set a vision and goals

- Time management

- Ability to work on a team

- Ability to work with people outside the organization

- Ability to manage others

- Career planning and awareness

The last four items in that list exhibited a skill gap for the respondents – they didn’t feel the PhD program had adequately prepared them for their work. It’s an opportunity for improvements in graduate training, and students should seek additional help.

For the other eleven skills, graduate training was helpful, making PhDs especially competitive in roles where data analysis, learning quickly, and communication are key.

And one more piece of good news from the study – PhDs appear to be pretty happy with their work!

When asked about job satisfaction, an impressive 80% of respondents said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs. This was true both for those in research intensive careers (e.g. faculty, industry) and those in non-research intensive careers (e.g. teaching, science writing)

“I was so encouraged by what I found. There is life after the PhD – life after the posdoc!” Sinche concluded.

You can read the entire paper at this link:

An evidence-based evaluation of transferrable skills and job satisfaction for science PhDs

Or read her book:

Next Gen PhD: A Guide to Career Paths in Science

Hazy Shade

This week, we also share a story about an assault on the hallowed tradition of anonymous peer review. After a legal fracas between Cross Fit Inc. and The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, a judge has ordered that the reviewers of a Cross Fit exercise study be unmasked.

We discuss the history of anonymous peer review, and why the current legal action is so unusual.

And we mellow out with the Purple Haze Lager from Abita Brewing Company in New Orleans. Hey, it’s Mardi Gras, someone throw us some beads!